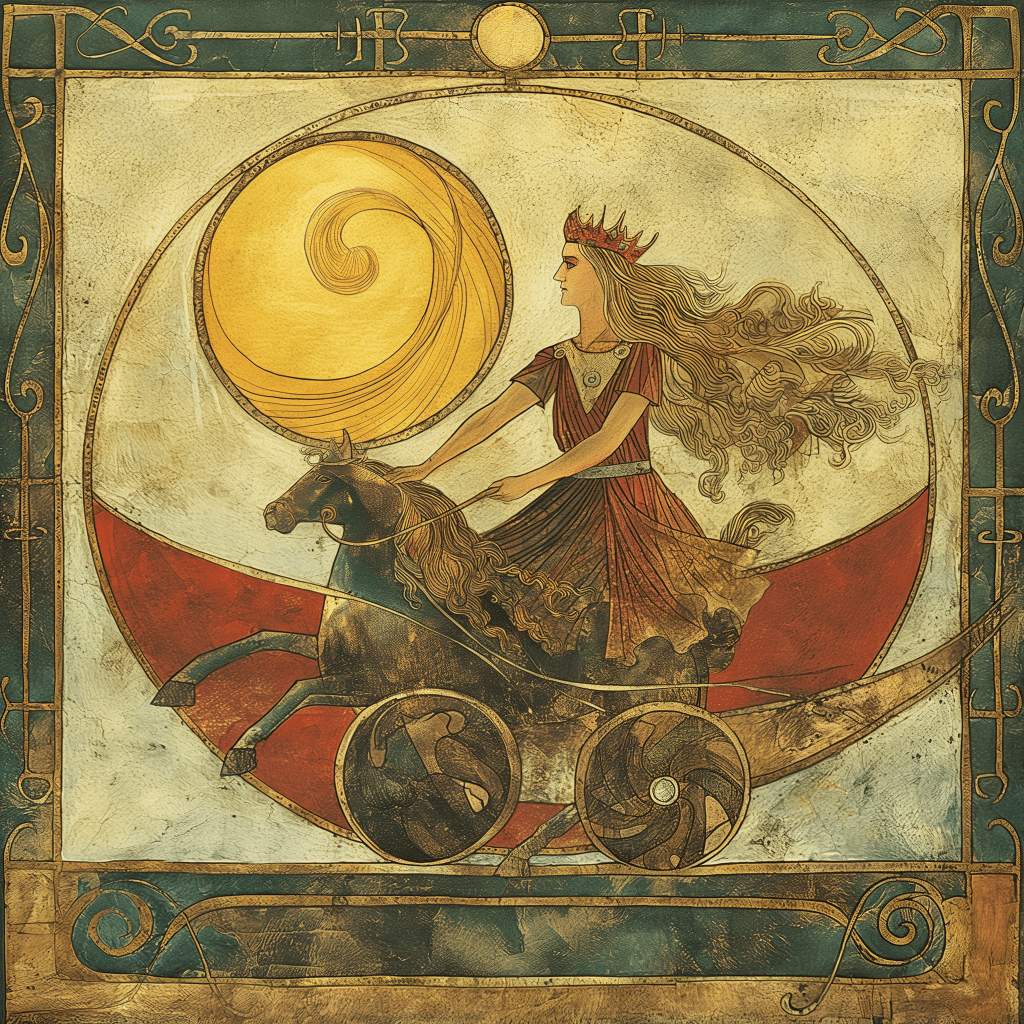

May Day marks the true climax of Spring and transition into Summer in the Northern regions. During this month, lots of plants and herbs begin to emerge after the long winter, bringing a plethora of flora and fauna to the land. On May Day, many Pagans resurrect (uncover) their idols of fertility and parade them through the towns and fields, blessing them for the upcoming agricultural year. In the past, this idol would have been housed in a cart or wagon and was presided over by specific individuals. Sometimes, these exclusive ritual participants were killed after laying eyes on the goddess in the wagon.

Jones & Pennick refer to this in “A History of Pagan Europe,” stating:

“The tribes around the mouth of the Elbe and in the south of modern Denmark are the ones who, as is now well known, worshiped Nerthus, Mother Earth. They saw her as intervening in human affairs and riding among her people in a wagon drawn by cows. The priest of Nerthus would sense when she was ready to leave her island shrine, and then with deep reverence would follow the wagon on its tour through the lands of her people, which would be the occasion for a general holiday, the only time when these warlike people put down their arms. At the end of the perambulation, the wagon and its contents would be washed in a lake by slaves who were then drowned. Noone was allowed to see the goddess on pain of death.”

In many cases, this idol was a goddess, and in others, a god would have taken its place, most notably Freyr. The idol that represented the god/goddess/spirit would be housed in the wagon, other times, a living person was chosen to embody the specific deity. Everyone would treat the person as if he/she was the actual deity themselves, dressing them in flowers and other pleasant things, parading them around in reverence.

Bonfires are customary during this time. Many people perform purification rituals using smoke and various other substances to cleanse themselves for the new year. Birch wood was most commonly used for these purposes and the smoke created would thus be walked through or “bathed” in. This was done to cleanse oneself and family of evil, sickness, and bad luck. Not only people, but livestock were said to be paraded through a pair of fires, ensuring a prosperous year, good health, and good harvests.

In “Celtic Mythology and Religion”, Macbain refers to the writings of Cormac:

“Most authorities hold, with Cormac, that there were two fires, between which and through which they passed their cattle and even their children. Criminals were made to stand between the two fires, and hence the proverb, in regard to a person in extreme danger, as the Rev. D Macqueen gives it, “He is betwixt two Beltein fires.”

Beltane bonfires are also referenced in “A History of Pagan Europe” by Jones & Pennick, where it says:

“The second great festival of the year was Beltane or Cétshamhain (1 May, May Day). This was the beginning of the summer half of the year, also a pastoralist festival. As at Samhain, the lighting of bonfires was an important rite. Cattle were driven through the smoke to protect them in the coming season. Beltane may be connected with the Austrian deity Belenos, who was particularly associated with pastoralism, or it may simply take its name from the bright (bel) fires which were part of its celebration. Beltane is the only festival recorded in the ninth-century Welsh tales, a time when the Otherworld communicates with the world of humans, either through portents such as the dragon fight in the tale of Lludd and Llevelys, or through apparitions such as the hero Pwyll’s sighting of the goddess Rhiannon.”

Later, around the 12th century, “May Baskets” became common practice in Germanic culture, which involved hanging flowers on strangers’ doorknobs or delivering flowers to friends, family, and the local community. This is still done today in many parts of the world, where people will anonymously leave flowers on people’s doorsteps in honor of the season. Essentially, May Day revolves around life, youth, and the beauty of the natural world around us. Through the blessing and beauty of the May Queen, we are propelled into the new farming season with inspiration and vigor.

As we can see from these various historical accounts, this particular event was of significant importance to not only Germanic and Celtic Pagans, but a pan-European celebration centered around a specific goddess, ritual cleansing, and Sun worship. Plenty of other cultures outside of Europe celebrate this occasion as well, such as some Native Americans, Persians, and Hindus. This renewal of life has been central to human experience for most of its history, promising us the glory of Summer and the proliferation of life.

In “Sorcery and Religion in Ancient Scandinavia,” Vikernes writes:

“On White Queen Monday they travelled the land to collect bacon, flour, eggs and other white food items for the large bride’s race. Dressed in white and wearing ribbons and wreaths of flowers they danced and sang all the way, from farm to farm, women and men, girls and boys, led by the king (alias the May King) and the queen (alias the May Queen), whether they were sorcerers or deities. The king and queen sat in a carriage, drawn by horses or the others in the procession. The queen did all the talking and the ladies and girls sang “Bride, bride, most beautiful bride”, to invite to the race all the women who believed they stood a chance at winning the bride’s race. The females in the procession wore men’s clothes on their upper bodies, and the men wore dresses, because they represented the hermaphroditic spirits. This custom remained even after the belief in spirits was supplemented with a belief in deities.”

On our homestead, May Day generally consists of uncovering our Freyr idol and walking him through the gardens and fields, either in a small mock-wagon or by hand. Once we have visited all the necessary areas, we return the idol to his altar and leave generous offerings for his blessings and fortune. Two fires are built in front of the altar and each ritual participant walks between them, purifying themselves of yearly baggage and giving personal thanks to the great Yngvi-Freyr. By doing this, each person can shed negative, dark, detrimental energies; inspiring wellbeing, clarity, and positive development.