Samhain is a time when the spirits of nature, the dead, and the gods are most likely to emerge to interact with the living. During these days, when daylight becomes shorter and shorter, nature around us seems to die and shed its vitality, leaving stalks, trunks and branches barren, resembling bones protruding from the soil. This is a time when we are meant to shift our focus from outdoors to indoors and shed our dead weight from the previous year, like the trees shed their leaves. By doing this, we are mirroring the process of nature and turning our energy inward. With Samhain come the final harvests, meaning that soon the workload will be drastically cut down and many daily activities will change. This time is to now be replaced with indoor tasks such as tending to animal pens, preserving food, repairing tools, spiritual practice, and performing various crafts such as woodworking, writing, or blacksmithing.

It is customary to make offerings to the deities, ancestors, and wandering spirits during this time in order to receive their favors, blessings, and good luck. We please the spirits to avoid their wrath. We offer to the ancestors to uphold family honor. We give our veneration to the gods to gain their power and visage. By performing rituals during this particular time of year, one enables themselves to better access various forces and gain insight into the past, future, and matters regarding cause and effect within the present which will aid one’s progress moving forward.

In “A History of Pagan Europe” by Jones & Pennick, they write:

“Samhain (1 November). This was the most important festival of the year, showing the pastoralist, rather than agricultural, origin of the calendar. Samhain was the end of the grazing season, when flocks and herds were collected together, and only the breeding stock set aside from slaughter. It was a time of gathering-together of the tribe at their ritual centre for rituals of death and renewal, dedicated to the union of the tribal god (in Ireland, the Daghda) with a goddess of sovereignty, the Morrigan, or, more localised, Boann, deity of the River Boyne.”

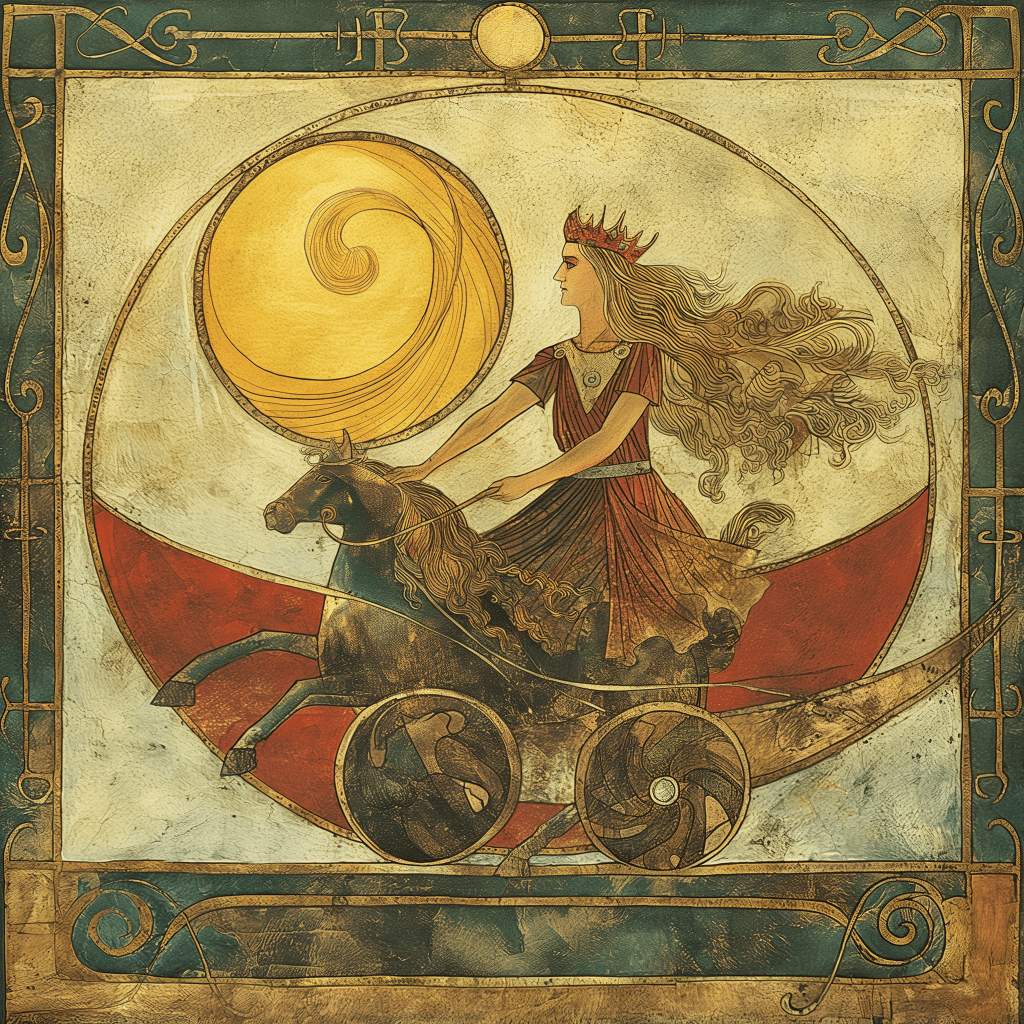

As the last of the great harvests, Samhain brings reward and celebration, the end of one year and the transition into the next. According to many European tribes, Samhain marked the turning point between the years and represented the New Year celebration of their cultures. With Samhain we descend into “night,” resembling the womb of the goddess or the abode in which she resides. The goddess reigning over this time of year was almost always in the form of a grim, fate-controlling hag or crone, such as Hel, Frau Holle, or the Morrigan.

In “Celtic Mythology and Religion,” Macbain writes:

“Equal to Beltane in importance was the solemnity of Hallowe’en, known in Gaelic as Samhuinn or ‘summerend.’ Like Beltane it was sacred to the gods of light and of earth; Ceres, Apollo, and Dis also, must have been the deities whose worship was honoured. The earth goddess was celebrated for the ingathering of the fruits; Apollo or Belinus and Proserpine were bewailed for their disappearing from earth, and Dis, who was god of death and winter’s cold, and who was especially worshipped by the Celts, as Caesar says, was implored for mercy, and his subjects, the manes of the dead, had special worship directed to them. It was, indeed, a great festival—the festival of fire, fruits, and death.”

In reference to Norse and Germanic paganism, we see the worship of elves and land spirits was also common during this time. In modern Germanic paganism, many people celebrate Samhain under the name Álfablót (Elf Sacrifice), which is when harvests are reaped and sacrifices are made to the elves and gods. Elves and the dead are strongly connected to the ancient burial mounds of the Pagans, therefore, much of the activity surrounding this festival would have likely involved distributing offerings to the gods and conducting sacrifices directly upon the mound (or grave) of the dead. This is where the elves were thought to reside.

In our own Samhain/Álfablót practice, the fair-weather god Freyr, king of the elves, is given one last celebration of reverence, being the center focus of the rites and rituals of the two-day celebration. He is invoked and offered substantial food and drink, as well as prayers and songs, showing devotion and thanks to the spirits and deities of abundance and prosperity. The event begins on the last day of October (Halloween) and ends the night of November 1st, when Freyr is returned to his resting place until the first of May. This cycle is reflected in “Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe,” where Davidson writes:

“He [Freyr] is said to have brought good seasons and prosperity to the land, and so when he died the Swedes brought great offerings to his mound, and believed that he remained alive and potent in the earth. The connection which seems to exist between Freyr and the elves and land-spirits thus provides an additional reason to associate them with the dead in their graves.”

Because of these associations, we place the death and rebirth of Freyr (the power of good weather and abundance) within this span of time (Nov 1-May 1). However, this is not the only way to do things nor is it recommended to everyone, as how one celebrates these sacred events revolves much around one’s lifestyle, geography, deity devotion, and overall means. For us in Western New York, this timeline coincides seamlessly with the natural cycle of the weather, and therefore is easy to follow. For those in a different climate or location, this may not make as much sense, and it is recommended to follow the patterns around you regarding these things.

In “Sorcery and Religion in Ancient Scandinavia,” Vikernes gives us further examples pertaining to the Nordic new year and pre-Christian Halloween customs. He writes:

“The first holiday of the year was New Year’s Day, better known in English as Halloween (“initiation evening”), and in Gaelic as Samhain (“summer’s end”). The sorcerers and later the gods (i, e. religious kings) and their challengers dressed up as different creatures with access to the realm of the dead. They fasted and hung their clothes in a tree or the gallows, to make it look as if they had hanged themselves. They wounded themselves with a spear, to bleed, smeared ash or white mud all over their bodies to look like the dead, they put on masks and sacrificed a cow or an ox on the grave mound, so that the blood poured down and into the grave underneath; into the realm of the dead. They then blew a horn, in the Bronze Age a lure, to open up the entrance to the realm of the dead. They then travelled into hollow trees, caves in the mountain, holes in the ground, or more commonly into the burial mounds. These were all seen as entrances to the realm of the dead. Inside, in the darkness of the grave, a woman was waiting for them, sprinkled in the sacrificed animal’s blood and dressed like the queen of death. They then took at least some of the objects their dead forebears had been buried with and brought them back out.”

As we can see, Samhain (or Álfablót) type celebrations were not only distinct to Celtic and Germanic culture, but rather appear as a pan-European tradition representing a celebration of the dead, the ancestors, and the final harvests of the year. It is clear that no matter which form of paganism(s) one practices, the celebration and event known to us now as Halloween is of very ancient and sacred importance. Not only as a transitional period between the seasons, but as a time when it was believed to be easiest to pierce the veil between dimensions and interact with beings outside of our normal cognition. It is because of the superstitions and Pagan worldviews of the past that we have many (if not all) of our current yearly celebrations in the West.