Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

An herb as powerful as Mugwort is an invaluable way to connect and learn more about Goddesses of not only Greek, but Norse and Celtic mythology. Mugwort and its association with women, those who protect and champion women, as well as those seeking to expand their metaphysical world through dream and deity work, is as important today as it was thousands of years ago.

Artemis, the namesake of Mugwort, is the logical starting point. Artemis is a goddess of the hunt, the moon, and especially of female initiation and protection. She is associated with girls and women, but is also a goddess to boys and men in rites of initiation and the hunt. All who wish to learn more and work with her are welcome, as she is a goddess for everyone. Mugwort, having derived its name from her, is the mother herb mirroring her mothering prowess.

However, in the Greek mythos, she was not a goddess to suffer fools gladly. She vehemently defended her virginity and reputation as the greatest of hunters. Some sources suggest she was the patron goddess of the fearsome women warrior tribe, the Amazonians. A passionate and ferocious fighter for what she believes is right, a beacon for those who need strength.

Of everything that Artemis is known for, Mugwort is most closely related to her powers as midwife, a deity for both comforting women in labor and the newborn. Mugwort is also an important herb for dream and trance work, lending itself nicely to moon rituals, as Artemis was also a goddess of the moon. Using Mugwort in its tincture form, or burning as a smudge stick, will help to expand consciousness and enter a trance state for magical work. Adding Mugwort into your meditation on Artemis during the moon, especially the full moon, will greatly enhance communication.

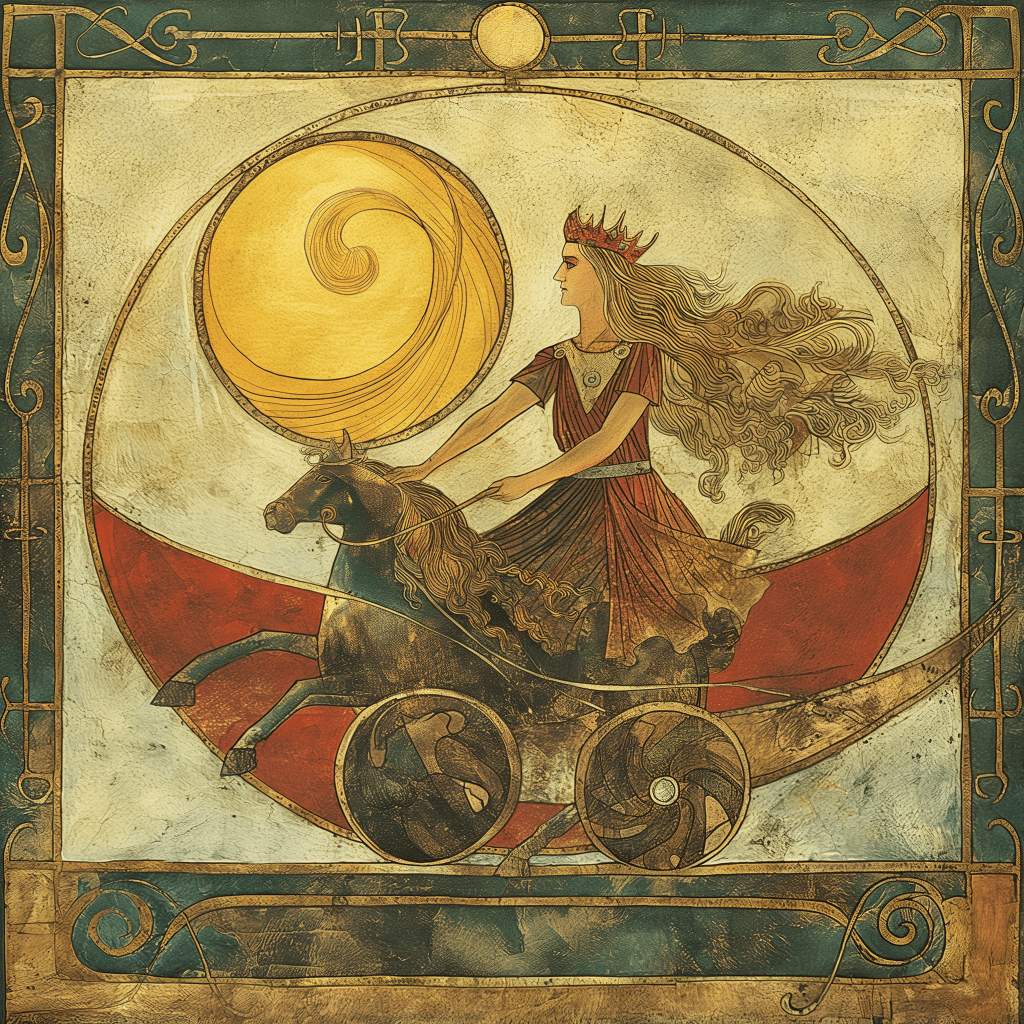

In Norse mythology, Frigg, the most powerful volva, was believed to be the first practitioner of seidr magic. Frigg is the wife of Odin and a fiercely protective mother of Baldur. She is the goddess of family, motherhood, fertility and the balance of love and wisdom. Mugwort works perfectly with Frigg as it is an herb whose main use has been for assistance in prophetic dreaming and the overall health of women.

Runes that can be used when invoking Frigg are Fehu, Pertho and Berkano. Fehu, when related to Frigg, is a female rune for fertility concerned with livestock, and especially newly born cattle in spring. Fehu is always a rune of productivity. It can also be used for spiritual or artistic creativity, carrying a fiery power within. Fehu can also represent certain aspects of the life force.

Freya Aswin correlates Pertho with birth. Pertho can also be used to help find hidden aspects within yourself. The joining of these attributes with Frigg, who governs birth and is involved with weaving fate (through work as a volva and through seidr magic), very nicely encapsulates the magic of Mugwort.

The Berkano rune indicates birth, being rooted, and the feminine, has been called a rune of ‘bringing into being’, the first protection given to children at birth. Both Artemis and Frigg were known as unrelenting defenders of children and women. Incorporating Mugwort when working with Frigg can be very beneficial.

The goddess of Celtic mythology most closely associated with Mugwort is Brigid. Brigid is known as a goddess of fire, poetry, and healing; a maternal goddess who embodies the divine feminine. She is like spring, representing new beginnings.

As a goddess of fire and hearth, she was said to watch over all the fires in the homes of Ireland. She was closely associated with the sun and the warmth of spring, the time of renewal and rebirth. Mugwort is also an herb closely associated with fertility, the goddess, and of womanhood. Brigid, as a goddess that protected the flame (which was so important for ancient people’s survival), is like a mother radiating maternal compassion.

Poetry (and creativity) have always had close ties with the metaphysical and dream world, a world that Mugwort works so well in. Brigid was called upon to help with creativity and inspiration, especially with bards, who held a very high position in Celtic society. Bards were the keepers of history and culture, and Brigid was often invoked to help inspire creativity.

Brigid was also a goddess of healing. She was often called upon to help cure sickness and injury, as her touch was said to have healing powers. In addition to being a healer of sickness and injury, she was a goddess of childbirth, watching over women in labor. Her presence helped ease pain and ensured a safe delivery. She was also a protector of children and was asked by parents to watch over children’s safety and health. Brigid and her divine energies align well with Mugwort and its properties.

The Autumn Equinox is the turning point in the year when daylight and darkness are equal once again, tipping the scales towards the darkest period of the year when the nights grow longer and the weather gets colder. Traditionally, harvests would be reaped during this time and various rituals were conducted for the gods and spirits residing over abundance. Attention was given to the wights and ancestors, as it was believed that this time was liminal and that other realms were accessible. At the cusp of Equinox, the dark half of the year begins to slowly gain dominance.

Bonfires are especially common as well as sacrifices, whether physical or symbolic. People give thanks and ask for future harvests, ensuring a healthy stock of goods for the upcoming Winter months. Much depended on this pivotal time of year and many rites were undertaken to guarantee success. Feasts would be widespread as well as games, echoing other Summer and Fall festivals in atmosphere. For us here in the Northeastern United States, many crops are ripening during this time such as squash, corn, and apples. With this comes canning and drying goods to stock pantries for the Winter.

In “Teutonic Mythology” by Grimm, it says:

“In some parts of northern England, in Yorkshire, especially Hallamshire, popular customs show remnants of the worship of Frieg. In the neighborhood of Dent, at certain seasons of the year, especially autumn, the country folk hold a procession and perform old dances, one called the giant’s dance: the leading giant they name Woden, and his wife Frigga, the principal action of the play consisting in two swords being swung and clashed together about the neck of a boy without hurting him.”

As seen above, many early English (and Germanic) peoples would honor the god/goddess Frieg (Frigga) and Woden (Odin) during this time. Woden/Wotan in early Germanic belief was sometimes associated with wheat fields, where offerings were left for his horse Sleipnir during pivotal moments of the year. Certain epithets of Odin give reason to believe that he has been worshipped as a benevolent god to some extent, reigning over wealth, fate, and general prosperity. Names like this include Farmatýr (Lord of Cargoes) and Óski (God of Wishes).

Regarding Odin and continental Pagan belief, Grimm also states:

“As these names [Woden/Mercury/Hermes], denoting the wagon and the mountain of the old god, have survived chiefly in Lower Germany, where heathenism maintained itself longest; a remarkable custom of the people in Lower Saxony at harvest-time points the same way. It is usual to leave a clump of standing corn in afield to Woden for his horse.”

Of all the ancient celebrations, the Autumn Equinox was the most difficult one to find any references for. My belief is that it was a lesser celebratory event and more centralized in each community, where the harvest would be brought in and the local spirits offered to. People were likely working hard and didn’t have time to prepare for anything extravagant like they would during the last harvest of the year (Samhain), which certainly would have taken the forefront in terms of importance, at least to the Pagan Celts.

In “The One-Eyed God” by Kershaw, it says:

“These times of transition are strange times, whether the transition is from month to month, or season to season, or year to year; they are times which are not quite one thing or the other. They are like boundary lines, which are not quite my property or yours, or doorways, which are not quite inside or outside. As Eitrem said, it is at these dividing lines of time and space that the dead and Hermes are particularly active.”

It was common to not only focus on the harvest at this time, but to also give special attention to the dead and gods (or spirits) associated with death. The year was about to start its descent into darkness and the deified Sun/Light was to begin the darkest part of its journey through the underworld. Because of this, symbolic bonfires are lit to emulate the Sun and prolong the light.

In “Sorcery and Religion in Ancient Scandinavia” by Vikernes, it says:

“Odinn placed his eye in the grave, in the well of the past, every year, in order to learn from the past. This might sound strange, but his eye was the Sun, Baldr, that lost its power every autumn and therefore had to spend the winter in the world of the dead. In other words, Odinn had one eye in the world of the living and one eye in the world of the dead.”

Aside from the various gods, goddesses, and spirits of prosperity, it is clear that Odin and Frigga took a central role in (Germanic) Equinox observances in some areas of Pagan Europe. Odin (Woden) was recognized as a god of wishes, death, darkness, gifts, and clairvoyance, mirroring the exoteric liminality of the period between light and dark invoked by the Equinox. This external event is to also be reflected internally, as darkness begins to gain supremacy after this transition. We begin to look inward and conduct deeper spiritual work, creating light within to combat the impending darkness of Winter.

Lughnasadh is named after the Celtic Sun god Lugh. This is a time when the first harvests of the year would be brought in and prosperity would begin to be felt amongst the community. Summer is fully in bloom and the golden fields and vibrant flowers mirror the glory of the powerful Sun above. During this time, people would feast and make offerings to the gods with the first fruits of the year. During Lughnasadh, there would be singing, music, games, competitions, and much more, as the people could finally begin to enjoy the rewards of their hard work so far that year. Traditionally, Lughnasadh is the first of the 3 great harvest celebrations, kicking off the sacred celebrations when humans reap the results of what they have sown.

In “Celtic Mythology and Religion,” Macbain writes:

“It is called in Scottish Gaelic “Lunasduinn,” in Irish “Lunasd,” old Irish “Lugnasad,” the fair of Lug. The legend says that Luga of the Long Arms, the Tuatha De Danann king, instituted this fair in honour of his foster-mother Tailtiu, queen of the Firbolgs. Hence the place where it was held was called Tailtiu after her, and is the modern Teltown. The fair was held, however, in all the capitals of ancient Ireland on that day. Games and manly sports characterised the assemblies. Luga, it may be noted, is the sun-god, who thus institutes the festival, and it is remarkable that at ancient Lyons, in France, called of old Lug-dunum, a festival was held on this very day, which was famous over all Gaul.”

Wrestling tournaments, races, and various games would have been held during this time in honor of the god Lugh, who is known for being highly skilled in many different areas. Archery, stone lifting, and weight throwing contests were said to have occurred, continuing into the modern day with summer events like the Highland Games. Sacrifices were also common in Pagan times, generally of a bull, and a feast would be made from its flesh, while a portion of the blood and other pieces were given to the gods.

In “A History of Pagan Europe” by Jones & Pennick, it is said:

“Lughnasadh (1 August, also called Bron Trograin) appears to have been imported into Ireland at a later date, perhaps by continental devotees of Lugh, who in the Irish pantheon is a latecomer, the ildánach, master of all skills, more modern in character than the other goddesses and gods. Correspondingly, Lughnasadh differs from the other three festivals in being agrarian in character, marking the harvest, and baking of the first loaf from the new grain. The deity honoured at Lughnasadh was Lugh, who was said to have instituted the games in honour of his foster-mother, Tailtiu. Tailtiu (Teltown) is in fact the name of the site of the festival in Tara. It is an ancient burial ground, and its name is thought to mean ‘fair’ or ‘lovely’, so if it ever was associated with a presiding goddess of that name, like Demeter in Greece she would have ruled both the Underworld and the fruits which sprang from it.”

In modern Germanic Pagan practice, Lughnasadh is recognized as Freyfaxi or “Frey Day,” replacing the Celtic Lugh with the Norse Freyr. Special and careful thanks are given to Lord Ingwaz/Yngvi/Freyr during this time to honor his power and acknowledge his benevolence. A general sense of peace should be felt on this day as well as an internal feeling of gratitude for all one has in life. As a god of wealth, Freyr makes us reflect on the things that make us feel a sense of prosperity in our lives.

In “Sorcery and Religion in Ancient Scandinavia” by Vikernes, it says:

“The 15th day of Alfheimr was Harvest Sacrifice (No. Slatteblot), also known as Wake-Up-Day, known from Gaelic as the festival of Lugh (“light”). The day marked the beginning of harvest. Before harvest could begin the grain spirit was killed and burned, or it was – in the shape of a goat made from last year’s straw – cut into bits and pieces and buried in the field’s four corners and in the field itself. By the time of the Bronze Age the spirit of light and grain had become a goddess and a god, Sibijo and Fraujaz, known from the Scandinavian mythology as Sif and Freyr respectively. The grain deity was still represented by a straw figure in animal form – usually a goat. In addition to this, the god was cut down with a sax, sickle or scythe in a sword dance. Finally, a symbol of the god, usually a loaf of bread or (in the most ancient of times) a cone, was cut into bits and pieces and buried with the straw animal in the field/meadow. The grain spirit had to die and be buried in the ground for new grain to come. They took the first straw harvested and made a new animal of it, then stored it in a safe place for next year’s Harvest Sacrifice.”

In summary, whether celebrating Lughnasadh or Freyfaxi, this is a time when the first fruits of the year are reaped and specific rituals are undertaken to ensure the fertility of the land. Skills are put on display and the community is brought together under a common aim: prosperity, happiness, and peace. It is important to give thanks to natural and local spirits for their blessings, and to the gods for their gifts. During Lughnasadh, we revel in the light, we feast, and we celebrate our good fortune.

Fehu is a rune denoting possessions, wealth, and material resources. In the ancient German tongue, this word would have represented one’s livestock, particularly cattle or other large production animals. Fehu stems from the Proto-Indo-European word péḱu, which translates to “livestock.” Before the common man was able to call land his own, the only things he could really claim ownership of were his animals, assets, and family. This would evolve later into the English word fee, meaning “a right to the use of a superior’s land, inherited estate held of a lord, general property ownership, money paid or owned, payment for service, a prize or reward.” We see this same idea in the Old French word fief, meaning “an estate held by a person on condition of providing military service to a superior, something over which one has rights or exercises control, or an area of dominion.”

Another connection we find relating to the concept of land ownership is in the word feudalism, meaning “a social system based on personal ownership of resources and personal fealty between a lord and subject.” This word can be broken down into 3 parts as “fe-odal-ism,” which would imply the connection between the noble (odal) and the fee (fe) one pays to essentially sub-lease land from the noble. This fee would be in the form of food, money, or military service. We also can find further evidence in the word fealty, meaning “allegiance to an oath to one’s lord.”

This rune applies to all things monetary and material, whether in the form of the living flesh of animals or in the cold medium of actual money. Fehu, in this regard, can also be assigned powers of security, abundance, domestication, opportunity, and peace. Esoterically speaking, one could view Fehu as a fire rune, as one’s resources are a type of fuel/fire source, helping to propel us forward with more confidence, and ultimately, more focus towards our goals. Now that we’ve peeled away the outer layers of the Fehu rune, we can look deeper inside for further information.

Connections can be made to the twin Vanir gods Freyr and Freyja, as this stave belongs to their respective “aett” of runes. Frey(r) has long been known to reside over the homestead, fertility, and success of the farm. His powers are attributed to fair weather, peace, prosperity, and general safety within the “sacred” or enclosed space of the homestead/village. Freyja, on the other hand, represents fertility, lust, beauty, death, and the Earth. In the “Old English Rune Poem” it is said:

“Wealth is an ease to every man,

Though each should deal it out greatly

If he wishes to gain, before his Lord, an honored lot.”

At this point in history, the author would have been referring to the Christian God. Nonetheless, this could easily refer to Freyr as well, and in fact clearly alludes to him, as the very title of Freyr means “Lord.” This poem, and others, also indicate a certain antagonism of greed, saying one must “deal out” wealth as much as he can do so.

We see another connection to Fehu and Freyr in the word fairy, which is generally believed to be a being connected with the dead, magical powers, and the natural world. This word is cognate with the Latin Fata, who is the goddess of fate. We also have the English word fey, meaning “dying, dead, spellbound, doomed, or otherworldly.” Here, we can see remnants of powers inherent in the fairy, but also in Freyja, as she is a goddess residing over the dead alongside Odin. This could be insight into the overall order of the Futhark, as one could assume it resembles a Ragnarök-esque circle of events, symbolizing birth, death, and rebirth. Some refer to this as “the doom of the gods,” which could be a possible piece of evidence alluding to the Fehu rune representing doom or death, perhaps hinting at the resurrection of ones “Self” by means of retrieving material possessions from the burial mound; in turn beginning a new cycle, starting with one’s possessions.

Suggestion for this can be found in “Óláfs Saga Helga,” where King Olaf facilitates his resurrection through the prophetic dreams of Hrani, who takes the possessions of his (Olaf’s) mound to the wife of Herald the Greenlander. After this, she then gives birth to a son who is bestowed the name Olaf, ensuring another life according to their tradition. The new Olaf would later denounce this claim, as Christian ideals had become the norm by then and the concept of reincarnation was abolished in their religion aside from select, “underground” sects. Similarities can be seen in the way Tibetans choose the Dalai Lama; who is shown past possessions to pick from at a young age. If the child chooses the correct objects, he will be recognized as the reincarnated Holy Man.

Freyr has also been associated with the burial mound, the dead, and the cult of the ancestors. In “Ynglinga Saga” it is said that after Freyr had died, he was buried in a great mound with 3 holes bore into it. Each hole was offered a precious metal of either gold, silver, or copper to ensure good seasons and peace continued throughout the land. In connection with the dead, it is said that King Yngvi also used to perform “utisetta,” or Norse meditation, upon his dead queen’s burial mound.

One more piece of evidence I will add, in this regard, is the Irish word figh, meaning “to weave together, compose.” Here we see the idea of a new beginning, the “weaving” of a new story, connecting with the ideas we explored in relation to the goddess(es) of fate, who have long been associated with the “spinning” or weaving of the destinies of man and the cosmos. This further ties the rune to the goddess Freyja, who is known for teaching seiðr to Odin; a sorcery generally associated with a metaphysical “weaving, tying, or binding” of a specific target, the weather, or the forces of fate altogether.

Through this very material and resourceful rune we can form a more broad picture of how it may have been used as it moved through the ages. From a purely terrestrial concept revolving around possessions and livestock to the more metaphysical aspect of fire, energy, and prosperity within the Self and tribe. We are also given objective history into the idea of land ownership and how that system is constructed based on the notion of leasing out lands to those below you in caste. The king leases his land to nobles and the nobles, in turn, lease their land to the farmers/peasants.

In conclusion, we can be assured that the Fehu rune is a rune of one’s material possessions and that it is a rune of moveable wealth. Further, it can be attributed to gifts of abundance, prosperity, and fertility of the Earth. As this rune moves through the times, it reflects not only money, but the fuel-source it represents in respect to our desires and opportunities. We see esoteric connections to the dead, the burial mound, and the Heathen process of reincarnation associated with the retrieval of “past possessions,” similar to that of the Tibetan practice. These rather obscure connections, upon additional reflection, seem to hold more and more weight within them.

The Summer Solstice is the time of year when the daylight is longest, the power of the Sun is at its peak, and the solar cycle reaches its apex, tipping the scales towards the dark half of the year once again. After this turning point, the sunlight begins to wane, shortening the daylight minute by minute until the Winter Solstice. Typically, this was a time to celebrate the Sun, spend time outdoors, and enjoy the bliss of good weather. Mead, wine, and other beverages would be consumed, and great feasts would be enjoyed.

In “Teutonic Mythology” by Grimm, it is said:

“Twice in the year the sun changes his course, in summer to sink, in winter to rise. These turning-points of the sun were celebrated with great pomp in ancient times, and our St. John’s or Midsummer fires are a relic of the summer festival. The higher North, the stronger must have been the impression produced by either solstice, for at the time of the summer one there reigns almost perpetual day, and at the winter one perpetual night.”

Games and various competitions would be hosted along with other festivities such as dancing and music. Entertainment would be lively and abundant, encouraging joy and merriment among the community. In the Germanic context, many people honor the god Baldr during this time as a god of light and/or personification of the light of the Sun, which in a mythological context, “dies” and beings to decline after this time, mirrored by Baldr’s death and descent into Hel. Because of these connections, a common blot/ritual focus during the Summer Solstice is the death (or funeral) of Baldr, the god of light. Stone ships are erected, abundant offerings are made, and various sacrificial items are thrown into fire. These offerings are meant to aid Baldr in his journey on the long road of the underworld.

In “Celtic Mythology and Religion” by Macbain, he says:

“The midsummer festival, christianised into St John’s Eve and Day, for the celebration of the summer solstice, is not especially Celtic, as it is a Teutonic, feast. The wheels of wood, wrapped round with straw, set on fire, and sent rolling from a hillock summit, to end their course in some river or water, which thus typified the descending course of the sun onward till next solstice, is represented on Celtic ground by the occasional use of a wheel for producing the tinegin, but more especially by the custom in some districts of rolling the Beltane bannocks from the hill summit down its side. Shaw remarks – “They made the Deas-sail [at Midsummer] about their fields of corn with burning torches of wood in their hands, to obtain a blessing on their corn. This I have often seen, more, indeed, in the Lowlands than in the Highlands. On Midsummer Eve, they kindle fires near their cornfields, and walk round them with burning torches.” In Cornwall last century they used to perambulate the villages carrying lighted torches, and in Ireland the Eve of Midsummer was honoured with bonfires round which they carried torches.”

Large bonfires and “Sun-wheels” are made during this time, reflecting the power and glory of the Sun. Special attention was given to the goddess during this time as well, whether as a deification of the Sun itself, the Earth, the Mother, or a mix of the 3. Offerings such as flowers, cakes, milk, honey, and blood are given to the gods and spirits, a ritual exchange of abundance for abundance. As observed in the above quote, it was (and is) common practice to bring the energy of the Sun down to Earth in the form of a torch, then parade it through the fields, groves, or temples in order to bless them with this powerful energy.

In “A History of Pagan Europe” by Jones & Pennick, it says:

“…But the summer solstice, under its statutory date of 25 June, became a popular festivity early in Germanic history. The German word Sonnenwende always refers, in medieval texts, to the summer solstice, not to the winter solstice. At the end of the first century CE some German troops in the Roman army at Chesterholme listed their supplies for the celebration in a record which has come down to us. In the early seventh century, Bishop Eligius of Noyon in Flanders criticised the chants, carols and leaping practised by his flock on 24.”

Here we are given examples of some ancient Germanic practices revolving around the Summer Solstice. We are told of singing, chanting, and competitive games like “leaping”. Clearly, the Christian Romans were disturbed by this revelry, showing its clear Pagan origins. This turning point in the year was extremely important to observe, as it strikes a pivotal moment in the Sun’s lifecycle, affecting every aspect of our lives.

The beginning of Spring is a magical time. Everything starts to wake up from Winter’s sleep, the air becomes perfumed by unfurling buds and shoots of green, birthed under sky and warming Sun. The birds start to unleash their full songs, filling the landscape with sound. In short, pure magic. What better time than now for one of the most magical plants to start its ascent skyward. Mugwort is now lining roads and walkways, growing unchecked in fields. I’ve taken the plunge into the world of Mugwort and would love to take you with me.

Mugwort (Artemisia Vulgaris) is one of the oldest herbs referenced in Anglo-Saxon plant wisdom. Some of its earliest known uses were to help regulate menstrual cycles, as well as with divination and dreamwork. There is also evidence of Mugwort smoke as an offering to Isis in Ancient Egypt. It has been mentioned in poems dating back as far as 3 B.C. in China, such as the the Shi King/Jing Poetry Classic. It is also mentioned in the poem “Hortulus” by Walafrid Strabo (808 AD – 849 AD), as ‘the Mother of Herbs’. Mugwort’s roots pre-date modern history.

The name Mugwort comes from the Greek Goddess Artemis, Lady of the Moon. She is the Goddess of hunting and fertility, also assisting in the cultivation of willpower and self-reliance. She is a comforter to women in labor, a helper to midwives, and protector of young girls. Mugwort is ruled by the planet Venus, lending it even more feminine energy. Hippocrates and Dioscorides even endorsed the use of Mugwort to help ease childbirth, their works having influenced modern medicine. The “Hippocratic Oath” that says “First do no harm” is from, well, Hippocrates.

The herb has many healing properties, both physical and spiritual. Physically, Mugwort may help stimulate menstruation, keeping from stagnation. It can be used for help in treating rashes, sore joints, bruises, and bug bites. Mugwort has benefits for pain relief, especially from arthritis. It has powerful nervine qualities, nervines being things that help relieve stress on your nervous system, which can be very helpful when treating anxiety, depression, and stress. Mugwort also contains things like iron, phosphorus, potassium, zinc, and tannin. It’s also a nutrient dense plant found most everywhere.

Personally, Mugwort is one of my favorite herbs. It has the ability to induce incredibly vivid dreams and the ability to bring about lucid dreaming experiences. Those are two of the main reasons why I love mugwort. Dream work is an important part of my spiritual practice, and Mugwort has been the best tool I’ve used. It can be taken as a tincture in tea, smoked, or put in dream sachets and bundles for burning. Being an herb so deeply entrenched in feminine energies, it is perfect for those that want to connect to the divine feminine, bond with their personal intuition, and enhance sensitivity. It can help open yourself to being more empathetic and patient.

Stagnation in body and mind can cause all sorts of problems. Mugwort increases circulation and warms the blood, helping a stagnating body. A stagnating mind will lead to frustration, detachment, and anxiety, just to name a few. Mugwort opens the mind, allowing for deep meditation and vision work. It can help with opening thoughts and deeper spiritual meanings. It moves the things in us which have lain dormant. It’s an herb for gentle but serious action.

Any phase of the Moon will work when using Mugwort for lunar practices, as it is a lunar herb. However, the best and most interesting time to use it would be during the Balsamic moon or when the moon is fully waned. The Balsamic moon is a time of going inward and recharging. This is the phase right before the new moon, making this moon perfect for meditation and really digging into the self. The Balsamic moon is the time to find what intentions you want to set and why you are trying to set that intention. Using Mugwort to explore your inner world will really help you bring your intentions to the surface; the perfect time to put your plans into action.

In Vedic astrology, eclipses are seen as a symbol of revenge or as a bad omen.

According to mythology, eclipses are caused by the Chaya Graha (shadow planets) Rahu and Ketu, who were once part of a divine serpent. The story is traced back to a time before creation in the tale of the churning of the ocean, known as the Samudra Manthan. The churning of the ocean represents our consciousness. After an awful and lengthy war, the devas (gods) and asuras (demons) cooperated to churn the galactic material called the Milk Ocean. The churning poured forth several gifts and treasures. They included the goddess of wealth Lakshmi, the wish-fulfilling tree Kalpavriksha, the wish-fulfilling cow Kamadhenu, and Dhanvantari, who carries a pot of amrita and a book of medicine called Ayurveda. Amrita is a Sanskrit word that means “immortality” and is a drink (or nectar) intended only for the gods.

A serpent demon (Svarabhānu) aspired to become invincible. Sitting between Surya (the Sun) and Chandra (the Moon), Svarabhānu disguised himself as a deva and managed to take a sip of Amrita during Samudra Manthan. Surya and Chandra recognized the imposter and informed Mohini (the female form of Lord Vishnu), preserver of life and order, who quickly decapitated him. As they were now immortal, Lord Vishnu needed to find a place for them, so he put them in two specific points in the sky.

The head of the serpent demon (without the body) became Ratu, who fell on one side of the sun. The tail without the head that fell on the opposite side of the sun became Ketu. The sun stopped all movement in order to keep Rahu and Ketu from meeting one another. Twice a year they can create confusion and exact revenge by consuming the Sun and Moon causing the world to suffer from darkness.Rahu swallows the Sun, and Ketu, the Moon. But only for a short while as the Sun and Moon have also taken in the amrita. Offerings of coal, mustard, sesame, saffron and lead are made to appease Rahu. For Ketu, offerings of lead, sugar, saffron and sesame are made along with offering food to a dog with black and white fur.

As seen above, eclipses can be seen as highly inauspicious. Light and power diminish which corrupts their positive qualities and creates disturbances in the natural order of things. It is believed that auspicious work should only be started in the light. Because of this, beginning any new ventures during this period of darkness is not recommended, as it can bring upheavals, obstacles, and turmoil.

#eclipse #vedic #astrology #rahu #ketu

The Spring Equinox marks the traditional Easter celebration, the moment when the Sun crosses the equator from south to north. This is when animals like rabbits, deer, chipmunks, and other creatures of the forest begin to have their offspring. Various flora also emerge around this time, dotting the landscape with hints of color. During the Spring Equinox we pay special attention to the great Goddess in her youthful form of Ostara, Goddess of the Dawn. Ostara is associated with the rising Sun in the East, fertility, and light; a beacon of joy and good fortune. To many ancient Germanic Pagans, Ostara was credited with Springs deliverance. From her name we derive the modern word Easter, nodding to the Pagan origins of this holiday. To Ostara we make offerings and pray for a good year, thanking her for the return of the light. In one particular myth, Ostara transforms a bird into a rabbit who would then lay colorful eggs for her, showing us where the core symbolism of our modern holiday came from.

Hailaz Austra!

#ostara #spring #equinox #paganism

In honor of the season and the veil soon thinning, I have taken to studying more macabre and spooky plant lore for fun.

I hope that you enjoy this first tale.

Hungry grass, also known as Féar Gortach is said to be a patch of grass that is indistinguishable from any other section of grass. However, it is said to be cursed by the dead that lay buried underneath.

Should you stand or walk upon hungry grass, you will be overtaken by weakness and hunger.

Variations of the hungry grass story tell of a person stepping upon the grave or burial plot of a victim from An Gorta Mór (the Great Famine) of the 1840’s. The Irish term “féar gorta” can be more accurately translated as “famine grass” rather than “hungry grass.”

This myth may be a folklore manifestation of the historical trauma suffered during the Great Famine (An Gorta Mór) of the 1840’s. When the Famine took hold, men, women and children were left to starve to death as a direct result of the Potato Blight and a misuse of resources under British Government rule at the time.

Over one million people died in poverty, starvation and agony. These poor souls were thrown into mass graves, usually in fields. These spaces became known as “Famine Graveyards”.

The grass eventually grew over the buried bodies and it was said to be cursed.

When scientific reasoning wasn’t particularly widespread, it was probably a fair attempt at rationalizing the unexplained deaths or episodes of fainting that would occur from time to time due to malnutrition.

An alternative version of the hungry grass tale relates that anyone walking through it is struck by temporary hunger. In order to safely cross the grass, one must carry a bit of food to eat along the way such as a sandwich or crackers and some ale.

In a few rare accounts, the hungry grass is said to actually devour humans.

There was the idea that the hungry grass may also eat crops too. Before the term “hungry grass” was coined, people thought that a spirit of a man was, in fact, eating people. The word “féar” in Irish is both “man” and “grass”. So, Hungry Man came to be because they feared him. It was said that if you give relief to Hungry Man, you will enjoy unfailing prosperity, even during the worst periods of famine and death.

Although the hungry grass superstition is outdated nowadays and seems very specific to Ireland, it has a lot of narrative appeal.

Beware the hungry grass!