Fehu is a rune denoting possessions, wealth, and material resources. In the ancient German tongue, this word would have represented one’s livestock, particularly cattle or other large production animals. Fehu stems from the Proto-Indo-European word péḱu, which translates to “livestock.” Before the common man was able to call land his own, the only things he could really claim ownership of were his animals, assets, and family. This would evolve later into the English word fee, meaning “a right to the use of a superior’s land, inherited estate held of a lord, general property ownership, money paid or owned, payment for service, a prize or reward.” We see this same idea in the Old French word fief, meaning “an estate held by a person on condition of providing military service to a superior, something over which one has rights or exercises control, or an area of dominion.”

Another connection we find relating to the concept of land ownership is in the word feudalism, meaning “a social system based on personal ownership of resources and personal fealty between a lord and subject.” This word can be broken down into 3 parts as “fe-odal-ism,” which would imply the connection between the noble (odal) and the fee (fe) one pays to essentially sub-lease land from the noble. This fee would be in the form of food, money, or military service. We also can find further evidence in the word fealty, meaning “allegiance to an oath to one’s lord.”

This rune applies to all things monetary and material, whether in the form of the living flesh of animals or in the cold medium of actual money. Fehu, in this regard, can also be assigned powers of security, abundance, domestication, opportunity, and peace. Esoterically speaking, one could view Fehu as a fire rune, as one’s resources are a type of fuel/fire source, helping to propel us forward with more confidence, and ultimately, more focus towards our goals. Now that we’ve peeled away the outer layers of the Fehu rune, we can look deeper inside for further information.

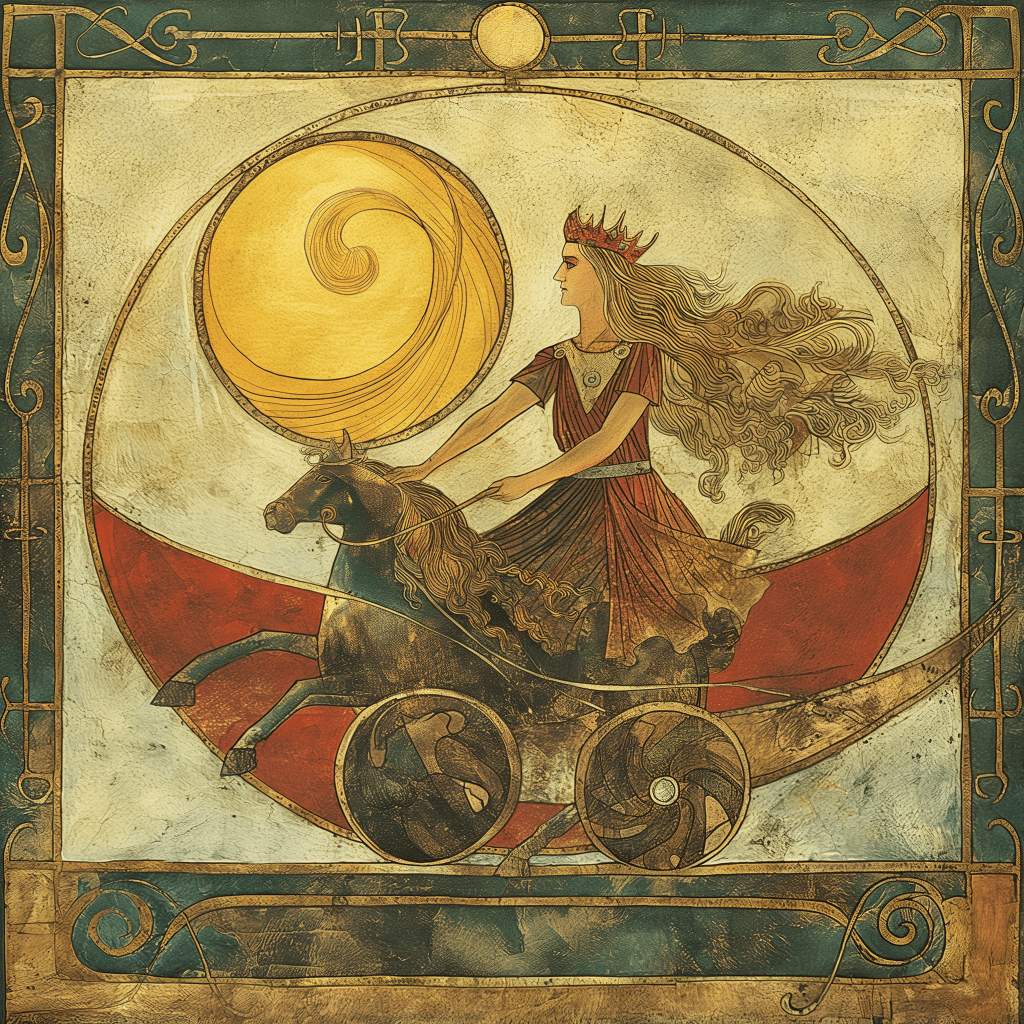

Connections can be made to the twin Vanir gods Freyr and Freyja, as this stave belongs to their respective “aett” of runes. Frey(r) has long been known to reside over the homestead, fertility, and success of the farm. His powers are attributed to fair weather, peace, prosperity, and general safety within the “sacred” or enclosed space of the homestead/village. Freyja, on the other hand, represents fertility, lust, beauty, death, and the Earth. In the “Old English Rune Poem” it is said:

“Wealth is an ease to every man,

Though each should deal it out greatly

If he wishes to gain, before his Lord, an honored lot.”

At this point in history, the author would have been referring to the Christian God. Nonetheless, this could easily refer to Freyr as well, and in fact clearly alludes to him, as the very title of Freyr means “Lord.” This poem, and others, also indicate a certain antagonism of greed, saying one must “deal out” wealth as much as he can do so.

We see another connection to Fehu and Freyr in the word fairy, which is generally believed to be a being connected with the dead, magical powers, and the natural world. This word is cognate with the Latin Fata, who is the goddess of fate. We also have the English word fey, meaning “dying, dead, spellbound, doomed, or otherworldly.” Here, we can see remnants of powers inherent in the fairy, but also in Freyja, as she is a goddess residing over the dead alongside Odin. This could be insight into the overall order of the Futhark, as one could assume it resembles a Ragnarök-esque circle of events, symbolizing birth, death, and rebirth. Some refer to this as “the doom of the gods,” which could be a possible piece of evidence alluding to the Fehu rune representing doom or death, perhaps hinting at the resurrection of ones “Self” by means of retrieving material possessions from the burial mound; in turn beginning a new cycle, starting with one’s possessions.

Suggestion for this can be found in “Óláfs Saga Helga,” where King Olaf facilitates his resurrection through the prophetic dreams of Hrani, who takes the possessions of his (Olaf’s) mound to the wife of Herald the Greenlander. After this, she then gives birth to a son who is bestowed the name Olaf, ensuring another life according to their tradition. The new Olaf would later denounce this claim, as Christian ideals had become the norm by then and the concept of reincarnation was abolished in their religion aside from select, “underground” sects. Similarities can be seen in the way Tibetans choose the Dalai Lama; who is shown past possessions to pick from at a young age. If the child chooses the correct objects, he will be recognized as the reincarnated Holy Man.

Freyr has also been associated with the burial mound, the dead, and the cult of the ancestors. In “Ynglinga Saga” it is said that after Freyr had died, he was buried in a great mound with 3 holes bore into it. Each hole was offered a precious metal of either gold, silver, or copper to ensure good seasons and peace continued throughout the land. In connection with the dead, it is said that King Yngvi also used to perform “utisetta,” or Norse meditation, upon his dead queen’s burial mound.

One more piece of evidence I will add, in this regard, is the Irish word figh, meaning “to weave together, compose.” Here we see the idea of a new beginning, the “weaving” of a new story, connecting with the ideas we explored in relation to the goddess(es) of fate, who have long been associated with the “spinning” or weaving of the destinies of man and the cosmos. This further ties the rune to the goddess Freyja, who is known for teaching seiðr to Odin; a sorcery generally associated with a metaphysical “weaving, tying, or binding” of a specific target, the weather, or the forces of fate altogether.

Through this very material and resourceful rune we can form a more broad picture of how it may have been used as it moved through the ages. From a purely terrestrial concept revolving around possessions and livestock to the more metaphysical aspect of fire, energy, and prosperity within the Self and tribe. We are also given objective history into the idea of land ownership and how that system is constructed based on the notion of leasing out lands to those below you in caste. The king leases his land to nobles and the nobles, in turn, lease their land to the farmers/peasants.

In conclusion, we can be assured that the Fehu rune is a rune of one’s material possessions and that it is a rune of moveable wealth. Further, it can be attributed to gifts of abundance, prosperity, and fertility of the Earth. As this rune moves through the times, it reflects not only money, but the fuel-source it represents in respect to our desires and opportunities. We see esoteric connections to the dead, the burial mound, and the Heathen process of reincarnation associated with the retrieval of “past possessions,” similar to that of the Tibetan practice. These rather obscure connections, upon additional reflection, seem to hold more and more weight within them.