The Summer Solstice is the time of year when the daylight is longest, the power of the Sun is at its peak, and the solar cycle reaches its apex, tipping the scales towards the dark half of the year once again. After this turning point, the sunlight begins to wane, shortening the daylight minute by minute until the Winter Solstice. Typically, this was a time to celebrate the Sun, spend time outdoors, and enjoy the bliss of good weather. Mead, wine, and other beverages would be consumed, and great feasts would be enjoyed.

In “Teutonic Mythology” by Grimm, it is said:

“Twice in the year the sun changes his course, in summer to sink, in winter to rise. These turning-points of the sun were celebrated with great pomp in ancient times, and our St. John’s or Midsummer fires are a relic of the summer festival. The higher North, the stronger must have been the impression produced by either solstice, for at the time of the summer one there reigns almost perpetual day, and at the winter one perpetual night.”

Games and various competitions would be hosted along with other festivities such as dancing and music. Entertainment would be lively and abundant, encouraging joy and merriment among the community. In the Germanic context, many people honor the god Baldr during this time as a god of light and/or personification of the light of the Sun, which in a mythological context, “dies” and beings to decline after this time, mirrored by Baldr’s death and descent into Hel. Because of these connections, a common blot/ritual focus during the Summer Solstice is the death (or funeral) of Baldr, the god of light. Stone ships are erected, abundant offerings are made, and various sacrificial items are thrown into fire. These offerings are meant to aid Baldr in his journey on the long road of the underworld.

In “Celtic Mythology and Religion” by Macbain, he says:

“The midsummer festival, christianised into St John’s Eve and Day, for the celebration of the summer solstice, is not especially Celtic, as it is a Teutonic, feast. The wheels of wood, wrapped round with straw, set on fire, and sent rolling from a hillock summit, to end their course in some river or water, which thus typified the descending course of the sun onward till next solstice, is represented on Celtic ground by the occasional use of a wheel for producing the tinegin, but more especially by the custom in some districts of rolling the Beltane bannocks from the hill summit down its side. Shaw remarks – “They made the Deas-sail [at Midsummer] about their fields of corn with burning torches of wood in their hands, to obtain a blessing on their corn. This I have often seen, more, indeed, in the Lowlands than in the Highlands. On Midsummer Eve, they kindle fires near their cornfields, and walk round them with burning torches.” In Cornwall last century they used to perambulate the villages carrying lighted torches, and in Ireland the Eve of Midsummer was honoured with bonfires round which they carried torches.”

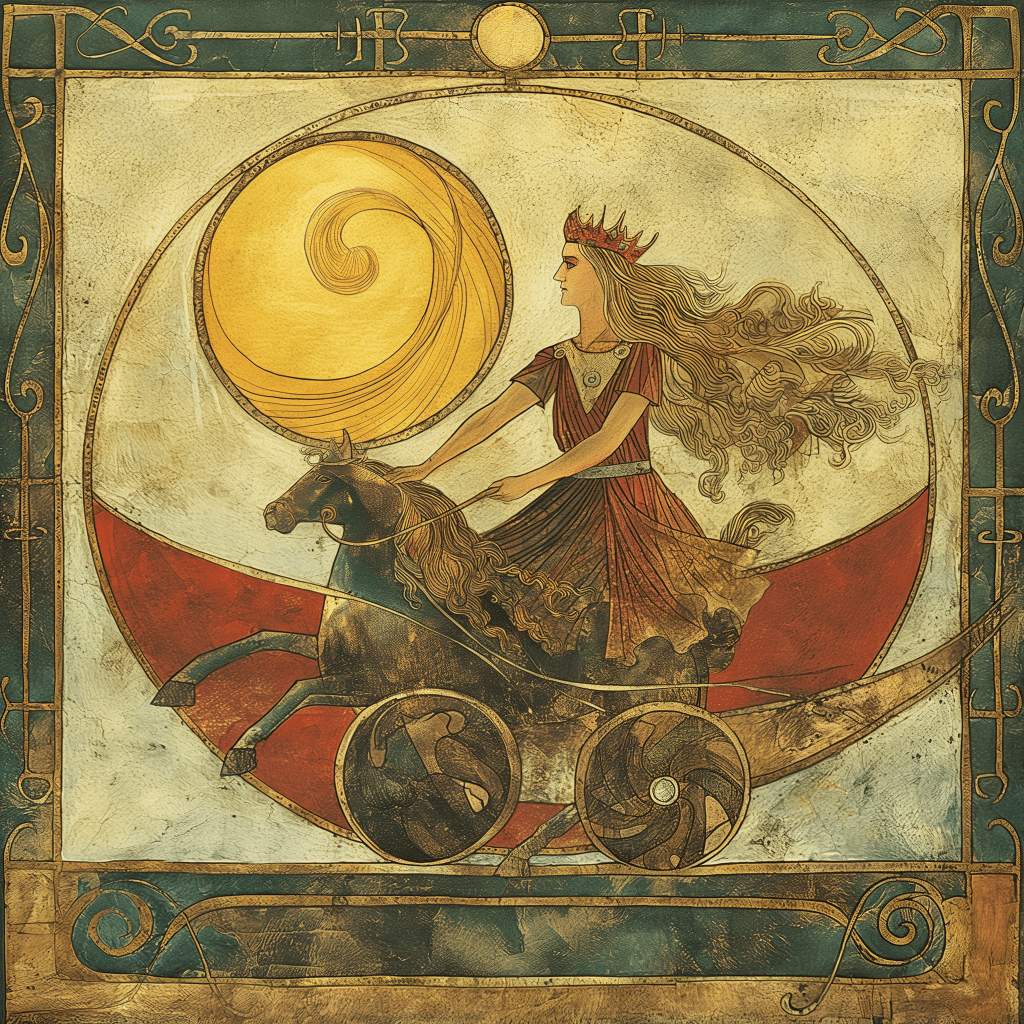

Large bonfires and “Sun-wheels” are made during this time, reflecting the power and glory of the Sun. Special attention was given to the goddess during this time as well, whether as a deification of the Sun itself, the Earth, the Mother, or a mix of the 3. Offerings such as flowers, cakes, milk, honey, and blood are given to the gods and spirits, a ritual exchange of abundance for abundance. As observed in the above quote, it was (and is) common practice to bring the energy of the Sun down to Earth in the form of a torch, then parade it through the fields, groves, or temples in order to bless them with this powerful energy.

In “A History of Pagan Europe” by Jones & Pennick, it says:

“…But the summer solstice, under its statutory date of 25 June, became a popular festivity early in Germanic history. The German word Sonnenwende always refers, in medieval texts, to the summer solstice, not to the winter solstice. At the end of the first century CE some German troops in the Roman army at Chesterholme listed their supplies for the celebration in a record which has come down to us. In the early seventh century, Bishop Eligius of Noyon in Flanders criticised the chants, carols and leaping practised by his flock on 24.”

Here we are given examples of some ancient Germanic practices revolving around the Summer Solstice. We are told of singing, chanting, and competitive games like “leaping”. Clearly, the Christian Romans were disturbed by this revelry, showing its clear Pagan origins. This turning point in the year was extremely important to observe, as it strikes a pivotal moment in the Sun’s lifecycle, affecting every aspect of our lives.